Rare Ghost Dance artifacts on display at county museum

Ed Kemmick/Last Best News permalink

Kathy Barton, the curator at the Yellowstone County Museum, looks at a Ghost Dance shirt owned by a son of Sitting Bull, the Hunkpapa Lakota holy man.

Ed Kemmick/Last Best News permalink

A pair of moccasins in the exhibit show wear marks from the side-to-side shuffling motion of the Ghost Dance.

Ed Kemmick/Last Best News permalink

On the left is a drum from about 1850, associated with an earlier religious movement developed by Smohalla. On the right is a drum that belonged to Fast Thunder, an Oglala Sioux.

Ed Kemmick/Last Best News permalink

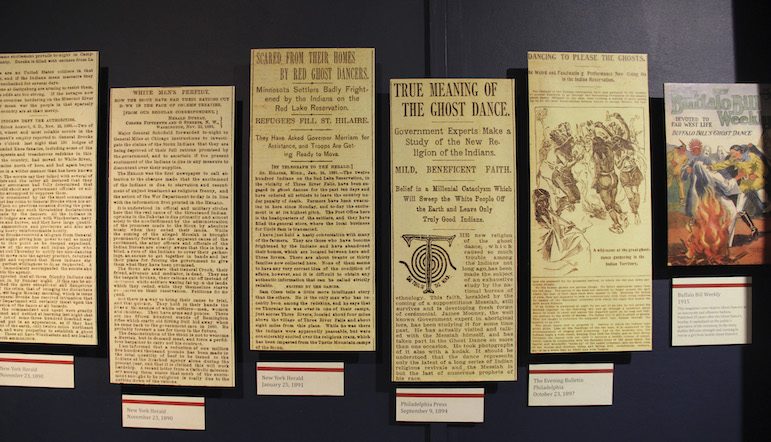

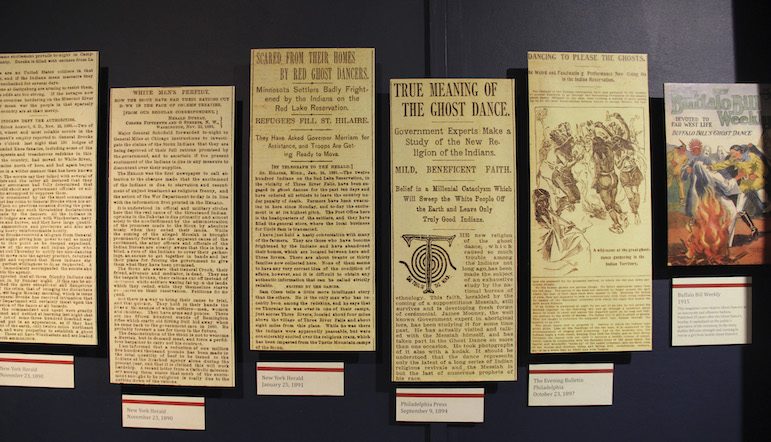

The exhibit includes excerpts of stories about the Ghost Dance from New York and Philadelphia newspapers in the 1890s, some of them fairly accurate and sensitive, some sensationalized and offensive.

The centerpiece of a new exhibit at the Yellowstone County Museum is a Ghost Dance shirt made for a son of Sitting Bull, but Kathy Barton’s favorite piece in the exhibit is a pair of Arapaho moccasins.

Barton, the museum’s curator, said the soles of the moccasins are clearly marked with a series of horizontal scratches, vivid testimony to the side-to-side shuffling motion that marked Ghost Dance ceremonies.

They are part of “Waiting for the Earth to Move: The 1890 Ghost Dance” exhibit that will have its grand opening this Saturday from 10:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. at the museum at 1950 Airport Terminal Circle, across from Billings Logan International Airport. As always, parking and admission are free.

The collection of more than 30 artifacts includes Ghost Dance shirts, dresses, drums, shields, pipes, a mink rattle, prayer staff and bags. It is on long-term loan to the museum from Billings native Larry Williams, who will talk about the collection once an hour during the grand opening.

“We don’t know of anywhere else in the world that has a collection of this size (of Ghost Dance artifacts on public display),” Barton said. “It really is kind of a big deal.”

Museum Director Matthew Fesmire, who came on board just two weeks ago, praised Barton for being “as knowledgable and thorough as she’s been with this exhibit. … Even though I’m new here, I’m proud to be part of it.” (For more on Fesmire, see related story below.)

Barton said Williams, who lives in the Virgin Islands, used to be more of a general collector of Native American artifacts, but he was so “awe-struck” by Ghost Dance items that he began collecting them exclusively. She said he did so to save them from disappearing into private collections that were not open to public display or available for research.

He reached out to the Yellowstone County Museum more than three years ago, remembering his childhood visits to the old-fashioned museum inside a pioneer’s salvaged log cabin.

As explained in the exhibit, the Ghost Dance was a religious movement developed in about 1890 by a Northern Paiute spiritual leader known as Wovoka. The Ghost Dance spread rapidly, reaching most of the Western tribes within two years. There were exceptions, Barton said: the Crow Indians never adopted it and neither did most of the tribes of the Columbia Basin and Pacific Northwest, who had their own, similar religious movement, developed by Smohalla, a Wanapum spiritual leader.

As Wovoka’s movement spread, the various tribes modified its ceremonies according to their own mythology and traditions. It was known by a variety of names, including Spirit Dance, Messiah Dance and Dance in a Circle, before becoming generally known as Ghost Dance.

Despite some differences, all Ghost Dancers looked toward the fulfillment of three promises, made in a vision to Wovoka by the messiah:

♦ Some cataclysmic event, ranging from a flood to volcanic eruptions, would destroy the earth, which would then be remade as a paradise.

♦ Buffalo and other game driven away by white men would return in great numbers.

♦ The dancers’ ancestors would be resurrected and live with them in the new paradise.

The Ghost Dance would take place at night for five or six nights in a row, the dancers adorned with elaborate painted designs on their faces and bodies. Different tribes wore different outfits during the dance, Barton said. Wovoka’s doctrines did not originally include Ghost Dance shirts and dresses. It is believed that Shoshoni and Arapaho Indians adopted the shirts and dresses from neighboring Mormons.

Ed Kemmick/Last Best News

A two-sided Ghost Dance doll represents this world—soon to be destroyed—and the paradise promised by the messiah.

The main thing was the dance, and the most striking thing about it, Barton said, is that it was open to all, with no restrictions as to age or sex. All danced in a big circle, holding hands or draping their arms over each other’s shoulders, shuffling from side to side as the circle revolved. The dance followed the pace set by the slowest participant, Barton said, often a young child or infirm elder.

Some dancers would enter a state of ecstasy and drop to the ground, go rigid and pass out. They were left undistributed, Barton said, because “they were now in the spirit world, communing with spirits.”

The Ghost Dance shirt at the center of the exhibit was made for Louis, one of Sitting Bull’s adopted sons. The shirt has not been shown publicly since 1975, when the Yankton Indian College in South Dakota closed and its museum collection was sold off.

Also on view from the Yankton museum are two drums, one owned by Fast Thunder, a Sioux warrior who rode with Crazy Horse, and the other by Two Strikes, an Arapaho warrior who had once met Wovoka. A third drum is older still, associated with Smohalla’s religious movement.

The exhibit, in the basement of the Yellowstone County Museum, has two sections. The first consists of explanatory placards and a few items not specifically related to the Ghost Dance. The Ghost Dance artifacts are in an adjoining display area, with curtains separating it from the first section.

Barton explained that some traditionalists are not comfortable viewing objects related to religious ceremonies, so they will be able to read about the Ghost Dance but not look at the actual artifacts. For similar reasons, Barton said, a special display case was created for this exhibit.

The case contains four drawers displaying pipe stems, bowls and bags, to be viewed at the visitor’s discretion. In some tribes, Barton said, women are not allowed to view sacred pipes.

New director hails from Alabama

Matthew Fesmire

Matthew Fesmire took over as the new director of the Yellowstone County Museum on a date heavy with historical resonance: June 6, D-Day.

The native of Huntsville, Ala., came to Billings from a job as director of the Belle Mont Museum State Historic Site in Tuscumbia, Ala.

Fesmire has a bachelor’s degree in history from Mississippi College in 2010 and in 2016 earned a master of arts degree in public history from the University of North Alabama. He described public history as a “practical form of history” that is designed to present history to the general public in a way that is accessible and easy to understand, that seeks to bring history to people who may not have known they were interested in it.

Fesmire said he saw an ad for an opening at the Yellowstone County Museum and applied because he was always intrigued by the West, though he knew little about it.

“I told some ofd the board members I’d never been west of Rosston, Ark.,” he said. “So it’s been pretty exciting.”

Driving to Billings was an amazing experience for Fesmire. When he finally saw the “unbelievable terrain” of Eastern Montana, he said, he realized why he must have been infatuated with the West, which he described as “something you have to see to believe.”

Since arriving here, he said, he has been immersing himself in the history of Yellowstone County, in keeping with the core focus of the museum, and trying to learn more about Montana history in general. He’s also been impressed with the reception he’s gotten here.

“Montana hospitality equals or exceeds Southern hospitality,” he said.

Comments

comments