Master beadworker combines traditional craft, inspiration

Ed Kemmick/Last Best News permalink

During a recent visit to Billings, beadworker Marcus Dewey shows a pair of moccasins he made. For more photos, click on the arrow at top right.

Ed Kemmick/Last Best News permalink

After attending a workshop about opportunities for capitalizing on the total solar eclipse this August, expected to draw thousands of people to Wyoming, Dewey came up with these beaded representations of an eclipse. He said he'll probably make earrings of the smaller pieces and a pendant with the other, and he hopes to make many of each.

Ed Kemmick/Last Best News permalink

Here's a close-up look at a pair of beaded moccasins Dewey made.

Ed Kemmick/Last Best News permalink

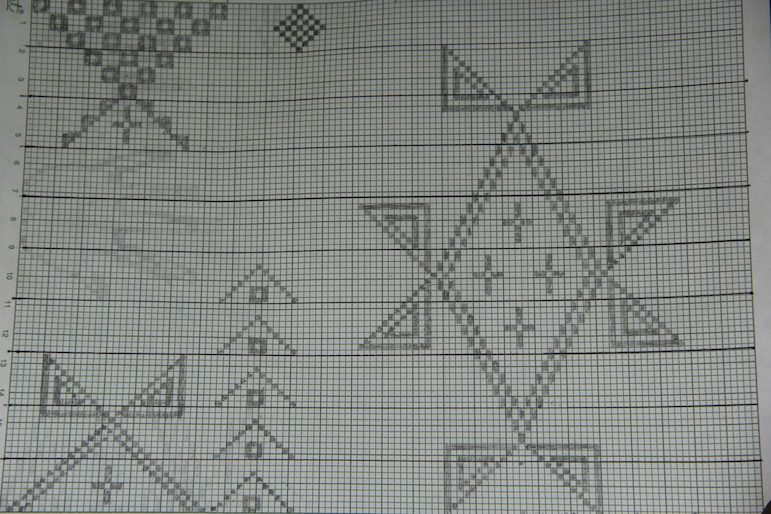

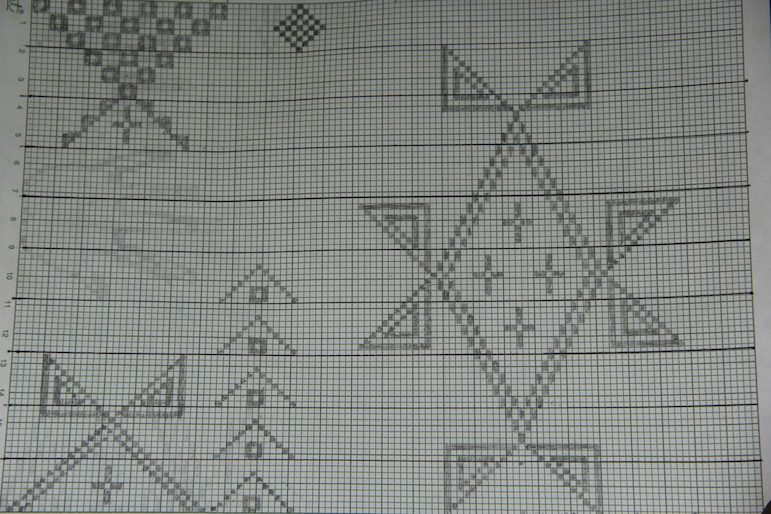

Dewey puts his designs on graph paper, each square representing one bead, before he goes to work.

Growing up on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, Marcus Dewey learned to do beadwork from his mother and grandmother. His grandmother’s most important lesson was a simple one.

“I always asked my grandma, ‘Is there an easier way?’ And she said, ‘No, there’s only one way.’ And that’s what she taught me.”

He listened and learned. And he practiced. Though he’d worked earlier in life as a ranch hand, truck driver and oil field laborer, Dewey has made his living exclusively off his beadwork since 1990.

Not only collectors value his work. The Plains Indian Museum of the Buffalo Bill Center for the West in Cody, Wyo., owns several examples of Dewey’s beadwork, including a vest, saddle blanket and saddle. The vest and saddle were acquired by the museum; the blanket was commissioned.

Dewey said a cradle board, like the one seen here, might take him three to four months to make.

The saddle and blanket are among a small number of pieces from the center’s six museums that are showcased in “Cody to the World!”, an exhibition celebrating the center’s centennial. The exhibit opened last Friday and will remain up through the end of January.

“Marcus is an amazing beadworker,” said Rebecca West, curator of Plains Indian Cultures and the Plains Indian Museum at the center. She said the saddle “is one of those pieces that really bridge the past and present.”

It uses a McClennan military saddle, in common use from the Indian Wars through World War I, as the canvas for Dewey’s beadwork, with traditional Arapaho colors of white, blue, red and yellow. It features pictographic images of a buffalo cow and her calf on either side of the saddle, along with symbolic representations of buffalo tracks.

Last Best News caught up with Dewey last week, when he was in Billings visiting his 19-year-old granddaughter, Tracie Dewey, who has been learning to do beadwork under his direction for years.

“She can do one moccasin and I can do the other and you can’t tell them apart,” Dewey said with pride.

Dewey specializes in moccasins, but in addition to the items held in the Cody museum, he has created beaded shirts, pants and leggings, pouches, earrings, medallions and more.

Years ago he worked at the Sundance Gallery in Billings, making beaded accessories for the clothing sold there. He also used to do the art show circuit around the West until he burnt out on that. Now he sells to individuals, dealers and gallery owners, some of whom sell his work on the internet. If it’s online, he said, he’s not involved in the sale, since he barely knows how to turn on a computer.

Dewey lives and works in Arapahoe, on the Wind River Reservation in west-central Wyoming. He mostly works in the Northern Arapaho style of his people, but he often uses colors and designs of the Sioux and Cheyenne, tribes that were closely associated with the Arapaho.

Besides learning from his mother and grandmother, starting at the age of 10, Dewey said he deepened his knowledge of technique and history from examining beadwork in the archives of the Buffalo Bill Center under Rebecca West’s predecessor, Emma Hansen.

By actually holding and studying traditional beadwork, he said, he could examine the stitching and patterns in ways that were not possible viewing beadwork behind glass.

That’s part of the Buffalo Bill Center’s mission, West said, “to have the collections available, especially to tribal members, to come and research. It’s important because it helps fill in the pieces of some the stories that are there but are not always available.”

Dewey bases many of his designs on traditional pieces he has studied or that were taught to him by older tribal members, but other designs come to him in his sleep.

“I dream designs, and then when I get up in the morning, I’ve got to get them on paper,” he said. Once he’s got some basic ideas down, he said, he can play with them, making adjustments and experimenting with colors.

Ed Kemmick/Last Best News

Dewey makes many kinds of beaded artifacts, but moccasins are his mainstay.

“I’ve got a blackboard in my mind,” he said. “I can put any color or design up there and see what it looks like.”

A pair of his moccasins might sell for $500 or more, which sounds like a lot until Dewey tells you how much work goes into each pair. He said he works eight to 10 hours a day most of the time, and it can take three or four days to make one pair of moccasins. A cradleboard, he said, might take three to four months.

One non-traditional technique of his is to put every design onto a sheet of graph paper, with each tiny square representing one bead. He said he’s amazed that traditional beadworkers could produce what they did without such a blueprint in hand.

When he travels, he carries a leather satchel with a portfolio containing photographs of hundreds of his creations, plus a folder jammed full of his designs on graph paper. He also keeps clients’ footprints for custom-made moccasins.

“Most everybody I’ve done moccasins for I’ve got footprints here on file,” he said, patting the satchel.

Because he knows so much about traditional designs and techniques, Dewey has been teaching beadwork for several years through the Wyoming Arts Council, but he said he also welcomes people who come to him on their own.

“A lot of people bead, but they don’t know the design or the color or what they mean,” he said. “That’s why they come to me.”

Comments

comments