John Warner permalink

Between classes, students crowd the hallway of the main building at Wyola School.

Last Best News (https://montana-mint.com/lastbestnews/2017/06/in-wyola-a-little-school-is-making-big-plans/)

Between classes, students crowd the hallway of the main building at Wyola School.

The school dominates the town of Wyola, which sits in a valley not far from the Wyoming state line.

Students get some exercise in the Wyola School gym.

Art teacher Maggie Carlson displays some of her students' watercolors in the school library, which sometimes doubles as an art room.

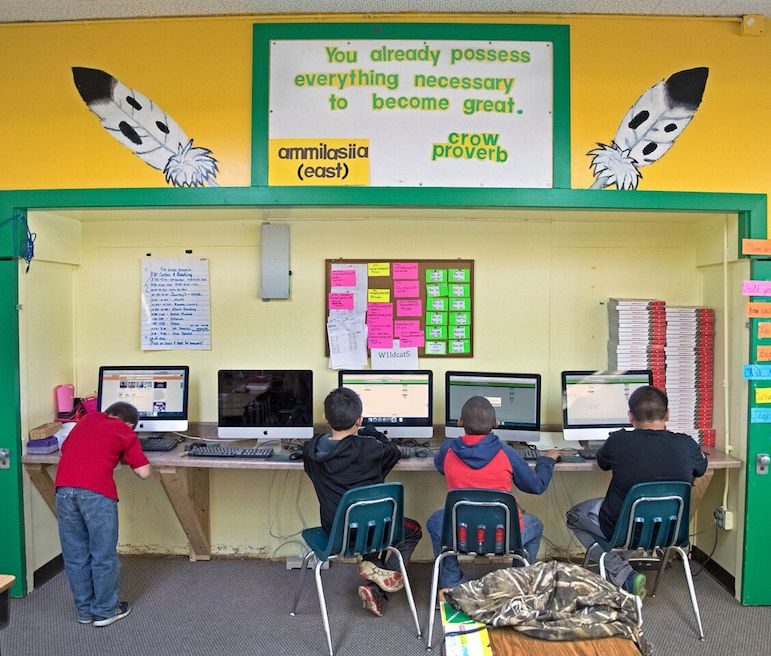

In Dorcella Plain Bull's fourth-grade class work at a computer station. When kids are doing web-based testing, every other computer on campus has to go off-line or the internet connection will fail.

WYOLA — It’s 9 a.m., the start of the day in Dorcella Plain Bull’s fourth-grade classroom at Wyola School. A drumbeat is playing over the PA and all of Plain Bull’s students are standing up and singing the Wyola district song, singing in the Apsaalooke language of the Crow Indians. They sing it every morning before reciting the Pledge of Allegiance.

Each of the six districts of the Crow Nation has its own song. The Wyola district song was written in the early 1960s by the father of Levi Yellowmule, the school’s athletic director. The song references “the Narrows,” a place north of the school, said to be the narrowest part of the Little Bighorn Valley.

“The people who live above the Narrows are good people,” the song says. “Go and visit them.”

“Most schools don’t sing their district song,” said Linda Pease, the Wyola superintendent, principal and substitute teacher. “We’re lucky. Our cultural program is stellar.”

That they sing it in Apsaalooke reflects the school’s commitment to preserving and promoting Crow culture. The people of Wyola, in turn, take great pride in their school, for good reason. The Wyola School is about all Wyola has left.

Over the years, one by one, little Wyola, population 215 as of the 2010 census, lost its bank, its train depot, its stores and its gas station. A new gas station and convenience store, owned by the Crow Tribe, burned to the ground in November, a month before it was expected to open. All there is in Wyola these days, besides a scattering of houses or the deteriorating remains of houses, is the post office and the school. The only public bathroom in town is inside the school.

The main school building is 60 years old this year, with four outbuildings—three modular and one stick-built—that have accumulated as the school has grown. Pamela Backbone, who teaches preschool there, said her great-grandparents, Richard and Ida Day Light, donated the land, 60 to 70 acres, for the school grounds.

The original school in Wyola was small, because so many local kids were going to school elsewhere on the reservation or to boarding schools in other states.“The parents were lonely for their kids in the winter months,” said Pamela’s husband, Bill Backbone, who serves on the school board. He said the Day Lights donated the land so local children could attend school close to home, and so their parents could have jobs.

It’s worked. Enrollment this year is 114 in the preschool-to-eighth-grade school. Most of the students are from Wyola or surrounding rural areas, but there is a sizable contingent from Lodge Grass, not quite 15 miles to the north. The school employs 15 teachers and numerous other aides and staff members. Pamela Backbone’s sister has been a school cook for years, her brother drives a school bus and her daughter-in-law works in the kitchen. The Backbones have two grandchildren attending the school this year.

“I think they envisioned that their children would go to school here and the families wouldn’t move away,” Bill Backbone said, referring to his wife’s ancestors. “It’s going on six generations now.”

Parts of the school are in rough shape, particularly the outbuildings, and much about the school has an air of improvisation about it—old bathrooms and janitor’s closets renovated into offices, instructional materials stored in crawl spaces, students crowded into one side of a classroom because the fluorescent lights on the other side don’t work. In one of the modular buildings, which has no storage, an extension chord and vacuum cleaner hang from hooks above the building’s only drinking fountain, with the floor brush resting inside the fountain’s bowl.

In another building, Pease points up at a smear of putty where the top of the wall meets the ceiling. She did the work herself, she says with a touch of pride.

John Warner

The main school building in Wyola is 60 years old.

The school is fairly well equipped with desktop computers and tablets, but the internet connection in Wyola, which sits about 10 miles north of the Wyoming state line, in the shadow of the Bighorn Mountains, is weak at best. When any class is taking state-mandated testing via the internet, or when web-based English proficiency classes are underway, every other device in the school has to get off the internet.

“Not even the secretaries can get on the internet,” Pease said. “If anybody gets on, the whole thing just shuts down. We learned that the hard way.”

As Pease leads a winding tour of the campus, though, neither she nor any of the teachers, aides or staff members complain. On the contrary, they all want to tell you how much they manage to accomplish despite all the obstacles and how much the school means to them and to the community.

Above all, they are proud of their role in preserving traditional Crow culture. Janice Wilson, the school’s Crow Studies teacher, has been an educator for more than 30 years. Teaching the Crow language is the core of the program, Wilson said, but she also teaches music, dance and sign language. She teaches the students about Crow clan systems, sacred objects, and about animals and plants and how they were traditionally used. And she teaches them to be reverent and respectful about what they have.

“All of these gifts that we have, like the tepee and the peace pipe, came by vision,” she said. “It wasn’t something that someone just thought up.”

As much as she loves what she’s doing, though, she’s also tired of being what she calls “itinerant.” Her tiny office is just down the hall from the music room in one of the outbuildings. She teaches some classes in the music room, which is handy, but many days she goes from classroom to classroom, building to building, a different one every hour, toting all her supplies and teaching materials.

“Sometimes I have to send students back to my office to grab this and grab that,” she said.

Maggie Carlson knows the feeling. She is the school’s art teacher, and the little office she once had was converted into the boys’ bathroom. The office she’s in now used to be part of a kitchen. Jammed full of art supplies, there’s barely room to turn around.

John Warner

Linda Pease, Wyola School’s superintendent, principal and substitute teacher, fields a question from a passing student.

Carlson, a native of Corvallis, Ore., had never lived on a reservation when she moved to Wyola in 1979, in a grant-funded position, to teach people to make functional, sellable pottery items. She soon met and married Bill Yellowtail, who went on to become a state senator, a U.S. House candidate and, under President Bill Clinton, regional director of the Environmental Protection Agency in Denver.

Except for the time in Denver, Carlson and her husband have lived on the Crow Reservation. Carlson has taught art off and on for many years in Wyola and spent eight years at Lodge Grass High School. She’s been back at Wyola for the past five years, and like Wilson, she often has to migrate from class to class, carrying everything she needs in a big cardboard box.

“This is quite a school,” she said, slowly shaking her head. “It’s held together with safety pins, I like to say.”

Fortunately, a lot of people outside of Wyola are also impressed by the school’s spirit, by its sense of resilience in the face of long odds. As a result, Wilson and Carlson could find themselves in much better offices by the start of the next school year, and teaching their arts and culture classes in spacious, permanent classrooms.

Pease started thinking more than a year ago about the possibility of finally having a building devoted to the school’s arts and cultural programs. She approached several members of the Scott family, founders of the First Interstate BancSystem and the Foundation for Community Vitality, about helping to fund the expansion. The Scotts, whose Padlock Ranch straddles the state line south of Wyola, agreed to help.

Based on that commitment, the school launched a $100,000 fund drive—though the total cost is expected to exceed that—to install a two-classroom, 3,000-square-foot modular building on school grounds. The new building would also have bathrooms, storage space, a kitchen and a gathering space for parents and tribal elders who visit the school to help with programs and projects, to share stories of Crow culture or just to visit.

Then, with help from Terry Zee Lee, of Billings, and her husband, Drake Smith, another major funder came on board. Lee and Smith, who had gone to Wyola School to lead a kite-flying program for the students, were distressed by the condition of the school, and when they heard of the fundraising efforts, they jumped in and obtained a commitment from the Denver-based Harry L. Willett Foundation.

More recently, supporters of the fund drive have been working with Bill Snell, director of Montana-Wyoming Tribal Leaders Council and president of the Pretty Shield Foundation. Supporters are also working with Pierce Homes, of Billings, to obtain the modular building.

Earlier this year, the supporters were reluctant to say exactly how large the commitments were, or exactly how much they needed, for fear of jinxing the deal or discouraging other donors. But they are convinced they’ll have enough to open the new building when school starts again in late August.

Pease said the steady expansion of the school is partly a result of changing educational practices, and partly owing to new needs.

Wilson, the Crow Studies teacher, can’t wait for the expansion. “This new building would really be heaven-sent,” she said.

Bill and Pamela Backbone see the addition as another way of prolonging the life of the school, of keeping it at the heart of their community. Even if they don’t get a gas station or a store, they said, as long as they’ve got their school, Wyola will survive. They don’t see driving to Lodge Grass, or down to Ranchester, Wyo. for supplies as a big problem.

“We’re used to it,” Bill Backbone said. “If we go somewhere, we’ll buy what we need. Kids don’t need to be spending money every day. They play basketball and they ride horses. We’re a quiet little town.”

This article first appeared in the Summer 2017 issue of the Montana Quarterly. If you’re not already a subscriber, you really should be. Check it out.

Pingback: First Time for Everything: Lost in Crow Country | Last Best News