Stapleton exhibit a stunning mix of old and new

Courtesy Stapleton Gallery permalink

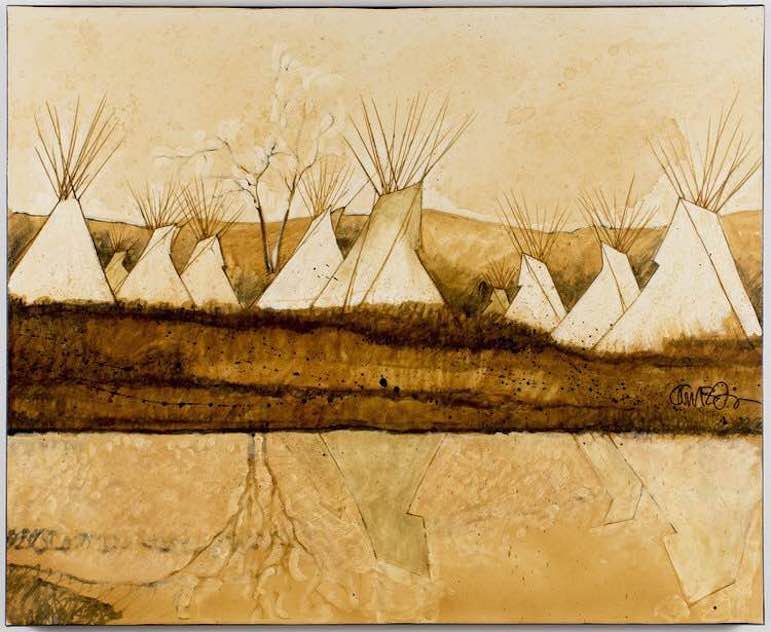

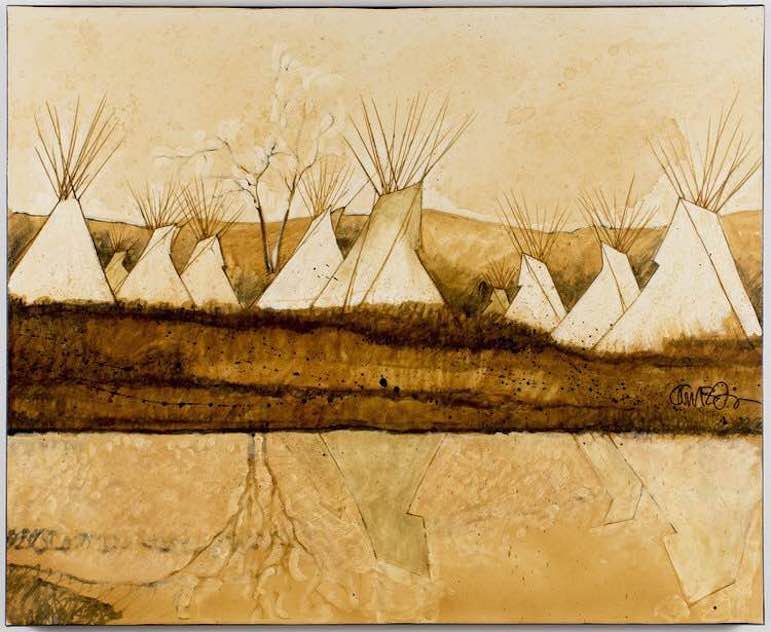

Kevin Red Star's "River Tipis," his interpretation of a photograph by Richard Throssel, is on display now at the Stapleton Gallery in downtown Billings.

Courtesy Stapleton Gallery permalink

Richard Throssel's untitled photograph of tipis on the Crow Indian Reservation.

Courtesy Stapleton Gallery permalink

Another untitled Strossel photograph from the Stapleton Gallery exhibit.

Courtesy Stapleton Gallery permalink

Erika Haight's photograph “Winds of Change” is a contemporary portrait of a Crow man sitting on his Appaloosa horse.

Courtesy Stapleton Gallery permalink

"War Dance," a photograph by Richard Strossel.

If I were to assess “Crow Now,” a collection on display at the Stapleton Gallery, based solely on its aesthetic impact, it would already be one of the best shows I’ve seen in a long time. But in this case, there is so much more of a story to tell. A story that goes back more than a century.

But first, we need to step back just a couple of years, to the time when Jeremiah Young took over Kibler and Kirch, a design firm that has developed a solid reputation in Billings for quality and class. When Young’s family bought the Stapleton Building a few years ago, the upper floors had been completely gutted, and Young saw an opportunity to do something special.

He knew the building at North Broadway and First Avenue North had a long history, including being the largest commercial building in Montana when it was built, and he decided to try to track down the original design plans, which they were able to find in Bozeman.

Young set about recreating the building just as it had been when it was originally built, and he came as close as possible, down to the fir floors, hidden doors in the wood paneled walls, and exquisite rugs, furnishings and even kitchen appliances that reflect that era. The process took more than two years.

Young moved his business into the second floor offices last year, but he wasn’t done yet. Behind the offices is a long hallway, leading to a sitting room, where Young envisioned something he’d always dreamed about, an art gallery. In June, the Stapleton Gallery opened its doors, announcing itself with a grand opening worthy of the best. Young isn’t shy about saying “I want this to be a world class gallery.”

The second exhibit may have just pushed them closer to that goal.

Enter Abigail Hornik-Minckler, Young’s partner in the gallery. Abigail is married to local historian and collector Thomas Minckler, who has one of the most impressive collections of Old West art and photography in the region. Among that collection is the work of a photographer from the early 20th century named Richard Throssel.

Throssel, who was part Cree, was raised in Washington state. When he visited Montana, he became enamored of the Crow Indian Reservation, and after getting to know the people there, he was able to gain their trust enough to be adopted by the tribe. This gave him unprecedented access to the reservation and its people, and the result of that was a collection of photographs taken in the early 1900s that show the Crow in their natural element.

Produced at a time when most photographers settled for stiff studio portraits, Throssel’s collection is a revelation, much like Evelyn Cameron’s photos of Eastern Montana. Throssel would eventually settle in Billings, where he set up his own studio, and he served two terms in the Montana Legislature. Minckler first discovered Throssel’s work back in 1979, buying his first Throssel “from a crack dealer,” and he eventually gained enough trust from Throssel’s family that his grandson sold him most of the collection.

Courtesy Stapleton Gallery

“Heart of the Mountain Crow” was painted by Ben Pease.

Abigail, channeling Thomas’s love of Throssel’s work, came up with the idea of featuring Throssel’s photographs. But she devised a unique way of doing so, a way that would tie the past to the present.

They held a dinner party in August and invited four of their favorite artists who focus on Native American culture. They then presented these four artists—Kevin Red Star, Ben Pease, Erika Haight and Judd Thompson—with the opportunity to choose their favorite photographs from Throssel’s collection, with the challenge of producing their own interpretation of these photographs. And they had just two months to do so.

The results are astonishing. “Crow Now” reflects the link between the past and the present in a way that is reverent, relevant and overwhelmingly positive. Red Star is arguably the most famous Native American artist in the region, and his work is generally defined by bold colors. But he breaks new ground in this exhibit with four paintings that pay homage to the black-and-white photos. These paintings, which he acknowledges to be a departure from his normal palate, are composed entirely of earth tones.

“River Tipis,” Red Star’s recreation of Throssel’s photo of a cluster of tipis pitched next to a river, is stunning. Red Star somehow depicts the reflection of these structures in the water using nothing but light browns. It’s an amazing example of meeting an artistic challenge head-on.

Judd Thompson shows substantial influence from Andy Warhol with his practice of producing several colorful versions of the same photograph. His best is a series based on the photograph of the famous Crow chief Curley, who bears a striking resemblance to Native American actor Wes Studi.

The series is called “Soul Survivor: See Him Speak, Hear His Story,” based on the myth that Curley was the only survivor from the cavalry directly under Custer’s command at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. These five paintings present an abstract of Curley’s portrait with various embellishments, including a series of stars circling his chest, and a mysterious red line framing his skull.

Courtesy Stapleton Gallery

Judd Thompson’s “Soul Survivor” features five paintings of the Crow chief Curley.

Like Throssel, Haight’s primary medium is photography, and because she has always made a point of getting her subject’s permission before she takes their photograph, she has also gained the trust of the tribe, eventually being adopted, giving her that same access Throssel enjoyed. The standout among Haight’s many wonderful photos is “Winds of Change,” a portrait of a Crow man sitting on his Appaloosa horse, wearing a war bonnet and little else.

There was apparently some concern about the fact that this man is not in the best physical condition, something I didn’t even notice until Abigail pointed it out. But in the end it was decided that this is exactly what has changed, and needs to be depicted as honestly as the beauty of the old ways.

But the centerpiece of this show is a painting by Ben Pease called “Heart of the Mountain Crow,” a 6-by-8-foot masterpiece that invokes the Native tradition of incorporating ledger paper into the work. Although it features very little color, the painting is a beautiful depiction of two overlying mountains, with tipis in the foreground of each.

The mountain in the foreground is dark, the tipis nearly lost in the shadow, but the tipis in back are lit up as if the sun has narrowed its focus to that particular patch of ground. The mountain gleams behind them, showing a wonderful contrast between light and dark, past and present, and finally, in the sky, the pages of an old ledger from a general store provides the contrast between commerce and Native ways. The piece brings together all of the elements of the show in one dramatic frame, and it’s breathtaking.

Minckler tells a wonderful story of a quote he found from Throssel’s writings, where he debunks the myth that Indians don’t like their photos taken because it takes a piece of their soul. “If they truly believed that,” Throssel said, “they would have simply photographed all of their enemies instead of trying to fight them in battle.”

As curator, Young does all the framing and presentation, and the show is beautifully arranged, with many of Haight and Throssel’s photographs filling the sitting room. It’s striking to notice how little difference there is in tone for these photographs, an indication that the show was intended to focus on the positive aspects of Native culture.

Between the history of this building, and that of the photographer, the work that these four remarkable artists produced provides a significant and timely story of how things have changed, but also how they have remained the same in the culture of this region.

Perhaps the most significant part of the show is how beautifully these images project both the past and the present in a favorable light. There is so much negative press about what’s happening on the reservations, and although some of that is valid, Native American culture is still very much alive and striving to move in a positive direction.

It’s heartening to see that effort displayed with such care and professionalism. For that reason, this show is not just impressive but very important.

Comments

comments